The February trip to Istanbul I'm about to describe was, as it was for most participants, our first excursion with Brno's Department of Art History. That's why we got on the plane in Vienna with a rather unclear vision of what awaited us, full of concern about the suitability of our footwear – multiple warnings that “we are going to walk a lot” left their mark. Just a few hours later, we had already landed in Turkey, taken a bus from the airport and arrived at the center, where we were supposed to meet the second group, on a later flight. Our first steps led us directly to the oldest part of Istanbul, called the Golden Horn: the area of the original ancient settlement and the heart of Constantinople since Constantinian times. After our two groups happily reunited and before going to find our hotels, we decided to wander around the evening streets. To wrap up this first day of the excursion, we went to have a delicious Turkish meal, ayran and tea – the first of many more we would enjoy.

Each morning, we met by the Obelisk of Thedosius, which stands on a former hippodrome. Today, it is a quite ordinary-looking square, which gives away its original function only in shape, the obelisk and fragments of a bronze column. The Hippodrome was situated right next to the imperial palace and served as a place for the emperor's public appearances. The ceremonial parade of an emperor and his family is one of the themes depicted on the marble relief base of the obelisk. Regarding the visibility limits of this object, we had a chance to test and find out that its relief decoration is clearly readable, even from a certain distance. Still, we can only imagine how the marble base looked originally, once covered by bright colors.

A short walk from the obelisk, and the main focus of our Saturday program appeared in front of us. “The” church, now a museum, the Hagia Sofia. We – first-year students – have been told that this visit was going to be a life-changing experience. That our life was going to be divided into the “time before visiting Hagia Sofia” and the “time after that”. Jokingly, of course. To begin this great encounter, we decided to spend the first thirty minutes in the relatively empty church on our own: just to look around and observe its features closely, to let the space and every detail of it impress us. And it truly was an impressive, breath-taking experience.

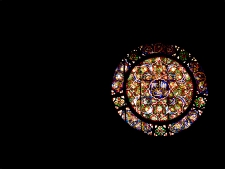

Following that, we spent almost the entire day in the Hagia Sofia, trying to fill the mesh of first impressions with some information. We talked about the church in terms of architecture and liturgy, focusing on the marble decoration and individual mosaics in the narthex, the apse and the galleries.

Although we could have spent hundreds of hours inside the Hagia Sophia and still found stimulating new things, worthy of our attention, we had to move on and see the Church of St Sergius and Bacchus. This building, said to resemble the Hagia Sophia on a smaller scale, now serves as a mosque. We had to pause our presentation of the building and complete it only after one of the regular daily prayers had finished. We went outside and spent a few minutes outside in the sun, listening to the singing of muezzins and watching the believers rush to join this suddenly re-animated “house of prayer”.

On Sunday, we went from the Hippodrome towards the Theodosian walls. Following this trajectory basically entails going from the very center of 5th-century Constantinople to its outermost borders. Besides the sensation that we had “physically felt the expansion of Constantinople in the 5th century” (here it should be noted that not everyone felt this with enthusiasm), during this walk, we also had the opportunity to admire extant remains of the aqueduct that supplied the city with drinking water. But the Theodosian walls were only the second barrier to surround the city: the inner line of fortifications, unfortunately not preserved today, was built already in the 4th century during the reign of Constantine I. The space between the Constantinian and Theodosian walls served as protected agricultural land – the city's inner resource of food and other supplies, in case of emergency or outside threat.

Our next destination, the 5th-century mausoleum called Silivri Kapi, was built in the same area, between the protective walls. But we actually arrived to an unpleasant surprise – access to the monument was completely blocked by a high fence topped with barbed wire. So, if we really wanted to visit the mausoleum, we could only do so at our own risk, trespassing. The ones who decided to climb over it (with Indiana Jones in mind) eventually ended up quite shocked, or at least with mixed feelings about the reward. On the one hand, it was a truly unique chance to look around the tiny space of the early Christian mausoleum and to observe fine reliefs on the sarcophagi, but on the other, the state of preservation of this centuries-old monument was simply miserable. As we were told later, the mausoleum was allegedly even more damaged than it was during the last excursion's visit four years ago – although by that time, it already quite blatantly served as an improvised homeless shelter. In this context, the fence and barbed wire suddenly seemed completely ridiculous.

Leaving the walls of Constantinople behind us, we headed back to the former palace area to see the church of Hagia Irene, the former cathedral of the city before the first Hagia Sofia – its sister church – was built. Although Hagia Eirene was never converted into a mosque or redecorated, one must depend significantly on the imagination inside of the church. Besides the famous simple cross in the apse, a few other small fragments of mosaic decoration in the narthex and ghosts of frescoes on the vault in the south aisle, not much of interior decoration has survived. There are only holes in the walls, recalling a rich marble revetment.

We spent the rest of the day at the Museum of floor mosaics preserved from the royal palace. We were enthralled by an abundance of animals, hunt scenes, mythological creatures, and even people captured in movement, suggestively standing out from the white-tesserae background. It was fascinating to examine the mosaics in such proximity: the amount of details and delicacy of color transitions the creators managed to render with tesserae measuring only few millimeters was simply outstanding. What is astonishing too, is the extent of these mosaics, which once covered the floors of the royal palace – the area almost of the size of a hockey field, as we calculated.

On Monday morning, in the hopes of a sunny day, we went to see the Church of the Holy Savior in Chora. Although it is not as voluminous as the Hagia Sophia, we spent several hours inside too – most of the time with our heads turned upwards, gazing at the gold-shimmering mosaics spread all over the ceilings of the inner and outer narthexes. We even tried to move around the narthexes in the same manner as believers used to while the church was still in use. We followed the rhythm and direction of stories narrated by the mosaics: we walked and stood still when necessary, in order to uncover and examine scenes from the life of Christ and Virgin Mary. It was an especially powerful experience when we kneeled, as in prayer, in front of a large wall mosaic that depicts Deésis. Only in this humble position does Jesus' and the Virgin Mary's gaze direct towards the onlooker. Unfortunately, we did not have an opportunity to admire the frescoes in the so-called parekklesion – a side burial chapel – which has been under reconstruction for several years.

We enjoyed our lunch on the street. One by one, we had a main course, Turkish tea, and even baklava for dessert. After the feast, we continued to the Church of Pammakaristos, where we came upon another disappointment. The church was not only closed, but was also surrounded by a high metal wall, so we did not see anything but a roof.

The last day was reserved for mosques. Since we had discussed it before, we knew about the desire of Muslim rulers to surpass the Hagia Sofia with their own houses of prayer. Inside the Suleiman Mosque, we had a chance to observe the differences and similarities and individual elements of the specific buildings in detail, and to compare their placement within the interior and function during the liturgy. Unfortunately, we did not have this possibility for the so-called Blue Mosque, which stands directly opposite the Hagia Sophia, tackling and surpassing the height of its dome by several meters. We were not really that surprised that it was also under reconstruction. So, we at least took a closer look at what we could see of the astonishingly colorful tiled decorations and headed to Istanbul's Byzantine Museum.

It might sound like a bad joke, but again, most of it was under construction. Some of us decided to spend the extra time in Hagia Sofia, but regrettably, we missed the closing time by four minutes. And not even Klárka's smile, or our heart-rending story that we were leaving the next day, were enough to soften the gate guard.

Fortunately, the end of this quite unlucky last day of our stay – our last night in Istanbul – was not so depressing. Quite the contrary. The dinner that we enjoyed together at the hotel's rooftop restaurant was absolute perfection. The city was spread out in all directions in front of us, the Hagia Sophia floating in a soft evening haze, as was the white-glowing mosque of the Asian part of Istanbul in the distance – everything in the palm of your hand. The icing on the cake was a traditional hookah. We filled the little room that had been assigned to us to the brim, and undoubtedly culturally enriched a gentleman who had already sat there before we arrived and refused to leave. But he changed his mind eventually – listening for twenty minutes to twenty voices singing Czech folk songs, not always harmoniously, but all the more enthusiastically, may have played a role in that. And we left long after he did. On the way back to the hotel, we went for a last look at Hagia Sophia, shining into the night and we symbolically ended our study trip.

Johanka Kalaninová & Lada Řezáčová